INTRODUCTION

Demise of Father Stan Swamy has hit the news channels and has been the headline of lot of newspapers. These headlines often hit us when we have ourselves suffered a loss, otherwise it’s just a page 7 news. This article is inspired by rejection of Stan Swamy’s bail application in May 2021. Swamy was arrested in 2020 from his house in Ranchi, Jharkhand over the pretext of his involvement in the Bhima-Koregaon Case in 2018. The question of him being involved during the Bhima-Koregaon violence is for the court to decide and the course of an investigation shall follow its determined route. However, after his demise on 5th July, 2021, a lot of questions pop up w.r.t to bail jurisprudence in India, and also makes one ponder whether timely access to medical care would have allowed Swamy to fight his case and prove his innocence?

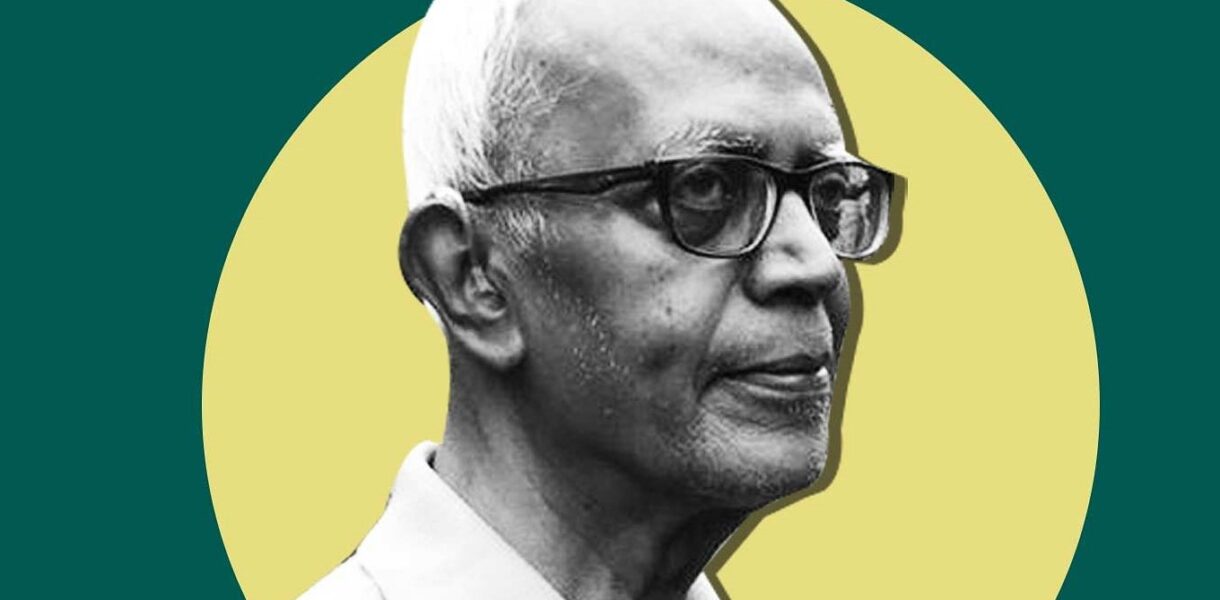

For those who don’t know Stan Swamy, he was an educated, Roman Catholic Christian who hails from Tamil Nadu and a former director of the Indian Social Institute, Bangalore. Swamy was not a silent spectator in life, rather he was vocal about his disagreements with government policies especially on rights of Tribal Groups. His arrest after the Bhim-Koregaon Case made him just another victim of mass suppression of dissent by the government. An 84-year-old man suffering from Parkinson’s disease, who was not able to do his daily chores without help, was undergoing trial and in Taloja jail. During the hearing, the court rejected the bail application and advised him to go ahead for treatment in a government hospital. Swamy rejected this compromise to go to a government hospital citing that the condition of JJ Hospital was worse off than a prison. He was later shifted to Holy Family Hospital in Maharashtra after he tested positive for COVID-19 and tragically succumbed to death on 5th July, 2021.

The author has taken the story of Stan Swamy as an example at bay to explain the intricate subject of bail jurisprudence in Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (hereinafter referred as UAPA.) and bring out its fallacy that leads to such unfortunate events.

QUESTIONING THE BAIL JURISPRUDENCE UNDER UAPA

The 268th Law Commission Report[1] that came out in May 2017, already warned us about the overarching detrimental effect that an extendable pre-trial detention can have against the principle of ‘presumption of innocence of the accused’, which is the very fabric of the criminal justice system. The rejection of bail application despite his deteriorating health, highlights this issue in the most concerning way. The ‘automatic denial of bail’, under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967, not only restricts a person’s freedom, but also their right to lead a healthy life.

Stan Swamy was left to suffer in an overpopulated jail in Maharashtra during the second wave of COVID-19. While international and national laws state otherwise, the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, famously known as Nelson Mandela Rules[2], and Article 21 of the Indian Constitution[3] and numerous other judgments point toward prisoner’s right to health while they are under-going trials. Whether it be the case of Shri Rama Murthy vs. State Of Karnataka,[4] or the Apex Court’s judgment in Charles Sobaraj v. Supdt Central Jail Tihar[5], or even the landmark 1981 decision in Francis Corahe Mullin v. The Administrator, UT Delhi[6] and an endless list of cases that highlight the importance of prisoner’s rights. With the deteriorating condition of Swamy, he was in need of a decent medical care which the Taloja Jail Administration could not provide.

According to Section 43D(5) of the UAPA, the court shall not grant bail unless there are reasonable grounds based on the charge sheet, case diary where the court believes that accusations are prima facie true. The problem with this is that the provision doesn’t give the scope of analysis to the judge after the evidence is submitted. In the case of, Zahoor Ahmad Shah Watali vs National Investigating Agency[7] , the court took an even narrower approach of this section, where the court didn’t even consider it necessary to examine if the evidence is admissible or not during the primary stage of trial. However, in the case of K.N Najeeb v. Union of India,[8] the Supreme Court held that Article 21 of the Indian Constitution shall prevail over any other law. The court further clarified that Part III of the Indian Constitution would cover protective ambit not only regarding the ‘due procedure’ but also access to justice and speedy trial. It was also held that legal provisions in UAPA that prohibit bail if there is a prima facie case against the accused, will not impede the courts from granting bail if fundamental rights are being violated. Varvara Rao, an 81 year old individual, also a co-accused in Bhim-Koregaon case, was also granted bail on medical and humanitarian grounds in February 2021.[9] Be that as it may, the question here needs to be asked, why are the courts forced into a corner to seek out the last resorts of Article 21, in order to provide an accused with the most basic of human and prisoner’s rights?

HOUSE ARREST AS A POSSIBLE ALTERNATIVE

The alternative of house arrest would allow the courts to offer vulnerable accused individuals, such as Swamy, with a remedy which doesn’t involve the likes of a prison and also fulfill the custodial needs, if felt necessary.

The Supreme Court while hearing the case of Gautam Navlakha v. NIA, [10]asked the legislature to ponder upon the concept of house arrest as an alternative to award of bail, and further highlighted that age, health condition, and antecedents of the accused along with the nature of crime shall be taken into consideration while grating their house arrest. Swamy was miserable during last few months as he claimed in his bail application and the same also been mentioned by his medical report by the Holy Family Hospital. The Apex Court also highlighted that deprivation of life and liberty during house arrest will fall under the provision of section 167 of the Code on Criminal Procedure, 1973. The court also referred to an article by J. Robert Lilly and Richard on “A Brief History of House Arrest and Electronic Monitoring” which highlighted the acceptability of practice of house arrest of political prisoners in India.

CONCLUSION

Indian bail jurisprudence states that “Bail is rule and jail is exception[11]”. Even in cases of Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act, 1987 (TADA) and Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985 (Para of 12 K.N Najeeb v. Union of India) the court has asked that trial should be speedy otherwise Article 21 will be invoked. The bench in the K.N. Najeeb case, made reference to Shaheen Welfare Association vs. Union Of India,[12] where the court held that, “Stringent provisions are kept in mind that trial will be speedy but no one can justify the gross delay in disposal of cases when under-trials, perforce, remain in jail, giving rise to possible situations that may justify invocation of Article 21.”

This article is not only an attempt to highlight the epithet situation which Stan Swamy went through, but also to point out to the readers that Indian prisons are not equipped with staff capable to deal with elderly prisoners and to provide them medical and psychological assistance when required. Further, Swamy’s story makes it more than evident that there is an urgency to provide a liberal approach to Section43 (D)(5) of UAPA, so that there isn’t another victim sacrificed at its hands.

Photo Source:The Quint

About The Author

I’m Sonal Beniwal, a law student and a passionate proponent of equal rights for all. I have a demonstrated history of working in Non-Profit Organization Management and Research & Analysis. Greatly interested in research on gender studies and SRHR.

References

-

268th Law Commission Report, Amendments to Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 – Provisions Relating to Bail, Page Number-16, May 2017 ↑

-

United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners – Nelson Mandela Rules ↑

-

INDIA CONST. Art. 21 ↑

-

Shri Rama Murthy vs. State Of Karnataka, ILR 1986 KAR 3037 ↑

-

Charles Sobraj vs The Suptd., Central Jail, Tihar, 1978 AIR 1514, 1979 SCR (1) 512 ↑

-

Francis Coralie Mullin vs The Administrator, 1981 AIR 746, 1981 SCR (2) 516 ↑

-

Zahoor Ahmad Shah Watali vs National Investigating Agency, CRL.A 768/2018 ↑

-

K.N Najeeb v. Union of India, 2021 SCC OnLine SC 50 ↑

-

Dr. P. V. Varavara Rao vs. National Investigation Agency, 1/92 53 Cri. Apeal-52.21 with WPs (01-02-21) ↑

-

Gautam Navlakha v. NIA, CRIMINAL APPEAL NO.510 OF 2021 ↑

-

State Of Rajasthan, Jaipur vs. Balchand @ Baliay, 1977 AIR 2447, 1978 SCR (1) 535 ↑

-

Shaheen Welfare Association vs. Union Of India, 1996 SCC (2) 616, JT 1996 (2) 719 ↑

Everything is very open with a really clear description of the issues.

It was definitely informative. Your site is very useful.

Many thanks for sharing!

Howdy very nice blog!! Man .. Excellent ..

Wonderful .. I’ll bookmark your website and take the feeds also?

I am satisfied to find so many useful info here within the publish, we want work out more strategies in this

regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

I think this is one of the most important

information for me. And i’m glad reading your article.

But want to remark on few general things, The website style is great, the articles is really excellent

: D. Good job, cheers

Hello very nice site!! Man .. Beautiful ..

Amazing .. I will bookmark your web site and take the feeds additionally?

I’m satisfied to search out numerous helpful information right here within the publish,

we’d like work out extra techniques in this regard,

thanks for sharing. . . . . .

I was suggested this website by my cousin. I’m not sure whether this post is written by him as

no one else know such detailed about my difficulty.

You are wonderful! Thanks!

I savor, cause I discovered exactly what I was having a look for.

You have ended my 4 day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a great day.

Bye

Pretty! This was an extremely wonderful article.

Many thanks for providing this information.