Today was the “Meeting Day”- when Geeta was supposed to go to the meeting centre, do home visits, and meet pregnant women. The 27-year-old is an Anganwadi Worker (centre for basic health care- under Anganwadi Services scheme) in Azamgarh district of Uttar Pradesh. Geeta is accustomed to going through five to six hours per day at work, away from home, yet this can ascend upto 24 hours when there are meeting days. It’s an impossible schedule. Moreover, she should wake up at dawn to bring water for her family, cook and clean for them, and work as an employed ranch hand during planting and gathering seasons.

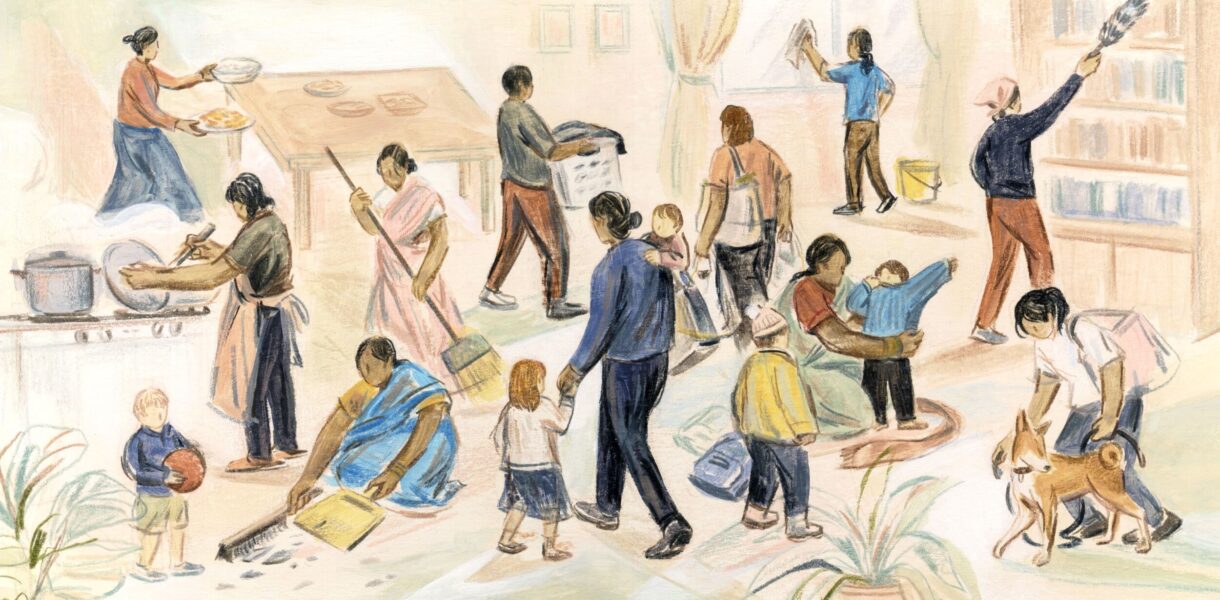

Today, universally we are managing the issue of neglected housework where women like Geeta lose the majority of their time, exertion and energy doing family tasks for their entire lives and left feeling unaccomplished. Closer home in India, in many relationships, the commonplace setting is to such an extent that men go out and do accomplished paid work and women sit at home to do unpaid family tasks. Notwithstanding, paying little mind to the hours of the day women put into this domestic labour , the work is regularly excused as a bunch of day by day tasks and not represented in either the GDP or the business measurements. Since the work done at home doesn’t really create products and administrations for the market, business analysts frequently overlook it in their estimations and the outcome is that an enormous part of the work done by women goes unnoticed as work and is treated as an obligation.

The relegated work carried by women turns into a debatable issue in a political decision.

Last December, Kamal Haasan assured a reimbursement to homemakers, as a thing of his ballot guarantees in his seven-factor management and economic plan, if his party, Makkal Needhi Maiam (MNM), is casted a poll to govern in the 2021 Tamil Nadu meeting elections. This guarantee to pay women a month to month sum is probably visible as a technique to seize interest in a huge constituency of voters- women who’re full time homemakers. MNM referred to their agenda, “The MNM authorities will take steps to realize Bharatiyaar’s dream of ‘Pudhumai penn’ through education, employment and entrepreneurship for women. Women will get through installation biased primarily based totally impediments by the equal probabilities given to them by our MNM authorities[1]”. Homemakers will get their due confirmation through agreement for their work at home which as of currently has been unseen and non-adapted, as a result elevating the pleasure of our womenfolk.

How was the idea accepted in the past?

In 1972, Selma James started the International Wages for Housework Campaign (IWFHC) in Manchester as a grassroots women’s network campaigning for recognition and payment for all caring work, in the home and outside. They needed to change the circumstance of reliance of women, invert the relations of influence, and rearrange the abundance that they delivered. Since the interest was for a pay ‘for housework,’ for any person who performed it, and not a pay ‘for housewives,’ it was in a situation to undermine the socio-sexual division of work. The “Statement of the International Feminist Collective” gave in 1972 in Italy, dismissed a division between unwaged work in the home and pursued work in the production line, articulating housework as a basic landscape in the class battle against private enterprise. All through the 80s and 90s, the IWFHC campaigned the United Nations Conferences on Women on neglected work, and got the UN to pass goals that perceived the unwaged caring work that women do in the home, on the land and locally. On March 8, 2000, women from more than 60 nations all throughout the planet took part in the Global Women’s Strike (GWS). This strike was called for by the Wages for Housework Campaign, requesting in addition to other things,” payment for all mindful work – in compensation, benefits, land and different assets[2].”

ILO characterizes neglected work as non-compensated work carried out to support the prosperity and upkeep of others in a family or the community, and it incorporates both immediate and circuitous consideration. Women in India spend in excess of nine times the time spent by men for unpaid care work. In real terms, this is what the sex divergence resembles – 297 minutes of women’s time a day contrasted with 31 minutes of men’s time a day. The hole is more extensive in metropolitan India as per Oxfam’s “Time is Up” report of 2020 dependent on overviews directed on 1,047 people. As per the time use information from the latest round of the National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO) 2020, women go through 238 minutes (four hours) more on neglected work every day than men in India. A regular women’s day begins at around 5 am and finishes after 9 pm. Hence, women possess little energy for themselves. It is assessed that the worth of women’s neglected family work adds up to almost 40% of India’s present GDP (worldwide, it is 13% of the economy). And still this work is peered downward in the world, and isn’t considered essential for national accounting or Gross Domestic Product[3].

Why is domestic work seen as the realm of women?

Albeit the Indian constitution awards people equal rights, a sturdy patriarchal system shapes the life of women with customs from centuries. Manusmriti, accrued around two hundred BC, units down how a woman’s existence is to be managed: A female is dependent upon her father in her childhood, then to her better half, and when her ‘ruler’ is dead then to her children.” Manu, the benefactor holy person of patriarchal society in the Indian setting, relates the chimney, the crushing stone, the brush, the pestle and mortar and the water-pot, with debasement/sin – all exercises that he additionally connected with women’s obligations. From wedding notices to TV serials, from movies to the local tattle factory, all celebrate “attractive” women, “great” housewives, who will deal with their families well. Young girls are customarily “prepared” for marriage by being trained how to cook from an extremely youthful age. The expression, “padhke kya karogi, chulha chowka hi to Karna hai” has been heard across geologies. A few juvenile young girls at the Voices from Margins online course series facilitated by Praxis Institute for Participatory Practices during the lockdown last year underlined the expanded weight of family tasks for little youngsters and the resulting sway on their examinations. Parents consider young girls to be liabilities and cause them to feel substandard compared to their male siblings. This strong patriarchal system makes it hard to eliminate the gender differences. These inconsistencies incorporate gender-specific early terminations, endowment passing, low instructive levels and high ignorance in women, notwithstanding gender differences in work openings and wages.

What do the critics say?

While there is an agreement arising on perceiving housework as work and crediting its monetary worth in public records, the possibility of pay for housework has been questionable. Women’s activists, who are pundits of wages for housework development, say that they are following a tight plan, which risks organizing the possibility of men as suppliers. They contend that the objective of women’s activist development ought to be to free women from the lopsided weight of housework and improve female independence through significant interest in the labour market instead of fortifying stereotypical social jobs. Some contend that the development is ‘traditionalist’ dependent on a bogus hypothetical reason. For example, they question if youngsters truly should be just seen as ‘future entrepreneur labourers’, for whose ‘creation’ women should be repaid with ‘trade esteem’. Hence, commodification, they say, can’t be a proper method to resolve complex social issues.

They also argue that women should be engaged at the fundamental level. Strengthening is tied in with engaging them in various ways – through schooling, learning and development. Strengthening can’t be just from the monetary part of things. One necessity to enable their characters. Women should be helped in creating more extensive abilities sets. This law might build up regrettable examples and adapted standards in the public eye.”

Who will come under this constituency?

Kamal Haasan’s stirring of the wap’s nest ought to be the reason for a lot further introspection. Is payment for work going to really raise the situation of women as contended? This further raises the question of who will be included in this constituency. Is it only for women who are full time homeworkers? Or women like Geeta who works outside of home and also performs bulk of household chores? On what conditions are they going to be included or excluded from the defined constituency? What about women who work from home and financially support their family by doing jobs like stitching, delivering home cooked meals or performing other petty jobs. They also term themselves as “Housewives”. These are issues that can’t be handily settled.

Other unanswered questions

Wages for housework additionally presents significant unanswered inquiries of operationalisation. First, who will pay the salary. Second, is paying the only way. Third and most challenging is how to gauge and value the worth of housework that should be paid as compensation. Adding one more layer to the contention, MP Shashi Tharoor connected wages for housework to the idea of Universal Basic Income (UBI). The idea necessitates that the public authority should ensure an all-inclusive essential pay for every one of its residents, paying little heed to their geography, work status or assets. The thought is to give a base living compensation to counterbalance fortuitous misfortunes, lessen destitution and advance equity. In any case, UBI is neither selected for women or homemakers nor it is in lieu of unpaid housework. Consequently it is pivotal to keep both distinguishable.

Way forward

Housework requests exertion and penance, 365 days every year, day in and day out. Notwithstanding this, a gigantic extent of Indian women aren’t “Queens” ruling over their realm, the family. An enormous number of women live with aggressive behaviour at home and pitilessness since they are monetarily dependent on other people, for the most part their spouses. It is thus important to perceive the worth of unpaid household work. Be that as it may, making esteem isn’t generally about reasonable compensation. Requesting that men pay for spouses’ household work could additionally improve their feeling of privilege. It might likewise put the extra onus on women to perform. Other than the morals of purchasing household work from a spouse represents a genuine danger of formalizing the male centric Indian family where the situation of men originates from their being “suppliers” in the relationship. More than making another arrangement of compensation for housework, we need to fortify mindfulness, execution and use of other existing arrangements.

Our point can’t be just to guarantee “fundamental pay” to women. Ladies ought to be urged and assisted with arriving at their maximum capacity through quality instruction, access and chances of work, gender-sensitive and provocation-free work environments and attitudinal and conduct change inside families to make family tasks more participative. When these conditions are met, working inside the home or outside should be a woman’s decision, an opportunity that she can practice for herself.

Conclusion

Wages for housework development politicizes an essential space of gender injustice and accurately brings up the requirement for women to deny unbalanced housework. Be that as it may, its technique to put a compensation cost on housework as a halfway step, before it tends to be denied, feels lost. Such measures, whenever taken on as strategy, could be costly social trials, with conceivable potentially negative results like an expansion in abusive behaviour at home or share requests. It is thus important to avoid policy shortcuts for monetary strengthening of women and spotlight should be on quality training, business openings and safe and savagery free open spaces.

Illustration by Sally Deng

About The Author

Kanan is a first year fellow at Gujarat National Law University. A writer by day and a reader by night. She is also a painter by passion and loves to try new things.

References

-

Samarender Reddy, It’s Time We Start Valuing Women’s Household Work By Paying Homemakers, THE WIRE (Dec. 10, 2021, 9:29 PM), https://thewire.in/women/its-time-we-start-valuing-womens-household-work-by-paying-homemakers ↑

-

Louise Toupin, The History of Wages for Housework, PLUTO PRESS ( Dec. 12, 2021, 12:15 PM), https://www.plutobooks.com/blog/wages-housework-campaign-history/ ↑

-

INTERNATIONAL LABOUR ORGANIZATION, www.ilo.org/asia/media-centre/news/WCMS_633284/lang–en/index.htm (last visited Dec. 16, 2021) ↑