In our society, expressions of love and affection – the deepest human emotions are viewed with scepticism. It is ironic though, for the love manifested in mainstream mythological stories such as the one of Krishna with Radha and other gopis is celebrated. Love is a way of life. Love and relationships are central to our being and acting in the world. However, in romantic love, only a certain kind of love, the one sanctioned by society and that which follows the rules and norms of endogamy is acceptable. How are these constructed social norms for love and marriage sanctioned, vilified, and reinforced in the larger culture? In this write-up, I attempt to comment on this social and political problem in our country.

One such contemporary construction which vilifies the Muslims is the “Love Jihad”. This theory targets Muslim men, asserting that they lure young Hindu and Christian women in the name of love and marriage, for the purpose of converting them to Islam. It alleges that “Muslim youth are receiving funds from [gulf countries] for purchasing designer clothes, vehicles, mobile phones and expensive gifts to woo Hindu women and lure them away” (Gupta 2009, 13). The innocent, gullible young Hindu women are lured by these flashy young men.

Love Jihad locates its argument on allurement by the Muslim man. It jostles with the idea of love itself. The Muslim man creates undue influence over the Hindu woman by giving gifts, the promise of a better lifestyle, romance, and gratification. Such means are purported to be fraudulent and therefore, the Hindus have to watch out for their women.

These claims of Love Jihad are not new. Gupta in her piece points out the ‘Shuddhi’ (purity) and ‘Sangathan’ campaigns led in the 1920s by the Arya Samaj and how they ignited communal clashes in Uttar Pradesh. At the time, the allegations were not limited to love and marriage, but also included abductions, rape, and elopement. Back then, the narrative was that women had to be saved from the hands of Muslim men. For example, major newspaper headlines read – ‘Hindu Auraton ki Loot’, ‘Hindu Striyon ki Loot ke Karan’ (Ibid.). Gupta draws parallels between the 1920s campaigns (mentioned above) and the ones of 2009. She points out the enduring image of infantilised women being victimised and Muslim men using them as tools. She argues that this conspiracy theory reinforces patriarchy, which allows the traditional Indian man to ‘reassert [himself] in the public-political domain in more forceful ways’. Further, that the Hindu woman is the sole preserve of the Hindu man who has the exclusive right and responsibility to safeguard her. Everything done by him under the pretext of preserving the family image is justified.

The feeling that the Hindu majority will soon be a minority has always pervaded the Indian subcontinent. These fears take various forms – attacks on mosques, protection of cows.

In 2009, various groups such as the ‘Vishwa Hindu Parishad and the Shri Ram Sena [claimed] that women in Kerala were being converted to Islam for the sake of marriage to Muslim men’ (Web source 1, EPW 2015). The High Court of Kerala at the time pushed the centre to come up with a law to prohibit ‘Romeo Jihad’ and observed that even though there was no solid evidence proving any such conspiracy, it can be deduced that ‘the programme was started in 1996 with blessings of some Muslim organisations’ (Web source 2, DNA India 2009). In 2017, the famous Hadiya Court Case occurred. It involved a couple from Kerala, where the Hindu woman converted to Islam after marriage. The High Court of Kerala carrying forward its observation from 2009 annulled their marriage. The Supreme Court restored their marriage finally in 2018.

The blame of conspiracy started again in 2020. Firstly, the state governments of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh put legislations in place – Prohibition of Unlawful Religious Conversion Ordinance and the Religious Freedom Bill respectively. These aim at curbing interfaith marriages and provide for a 10-year jail term if found that the marriage was for the purposes of conversion (Web source 3, Indian Express 2020). Secondly, a hashtag calling for the boycott of a big jewellery label trended on social media for promoting this conspiracy through an advertisement. This sparked a lot of outrage and one of the stores and its staff of the jewellery retailer was attacked.

The Love Jihad allegation stems from various social prejudices. First, the hatred towards the minority, which arises from the fear of the tables being turned for the majority. It is projected that the share of Hindus in the demography of the country is steadily declining and that of Muslims is increasing. Since partition, Hindus have tried to paint the common Muslim man as an enemy. The enemy is seen as consuming the sacred cow, destroying the temples, trying to conquer territory or the punya bhoomi, seducing and abducting women. In addition, the enemy also plans to convert the majority (Hindu) members to Islam followers through conversion. The Muslim man is demonised as a sexual predator, lustful and filthy. These attacks tend to unite everyone against one common enemy, rendering it politically irrelevant. The belief that there is a conspiracy in place to produce large numbers of Muslim children is gaining popularity. For the same, it is considered that handsome Muslim men are deployed as tools. Further, that they receive funds from the Gulf countries for the spread of Islam.

The second prejudice from which this allegation stems is that of honour. One of the most historic ways of ripping a country of its honour is by raping the women of that land/ community. Every conquest in history has included ownership of land, jewellery, and women. A woman’s purity is a symbol of a family’s and the nation’s honour. This has been exploited by both majority and minority communities alike. The 1947 partition witnessed one of the most horrendous religious riots in history. It included rapes of multitudes of women. Many women jumped into wells or eloped into forests to safeguard their honour. Chakravarty (1993, 579) shows through historical evidence how ‘women are gateways – literally points of entrance into the caste system’ and therefore, are used to maintain social order. Using a woman’s honour to establish religious dominance is what evilizes an interfaith marriage to this day. This propagation of women as a ‘fertilizing tool’ for the minority to increase their number in the demographics has dual purposes. The first, as mentioned above, to evilize the minority. Second, to instil fear in women and continue the patriarchy. The narrative that they cannot be independent but have to depend on the man for protection and that they cannot make a choice of their marriage partner is legitimised through this fear.

Two members of the Constitution drafting committee, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur and Hansa Mehta argued for the guaranteeing of this right of choice to a woman. Even though Gandhi supported it, most of the committee members were opposed to it. Even Ambedkar felt that our society was not ready for it. Thus, it prevailed that Indian women are not given the right to marry the person of their choice. This essentially not only forbids marriage by choice but also the ability to think for oneself. Women are seen as helpless, gullible, and incapable of making their own choices. If a woman defies such constructed boundaries, and ‘brings shame’ to a family she is often met with social sanction and even violence in the form of honour killings.

The legislation in Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh places the burden of proof on the individual and not on the executive. The individual has to justify personal choices to a state authority. A couple has to take prior permission from the district magistrate to marry, extending the burden of approval from the family unit to the state as well. The man and woman have to prove that their love is not luring, it is not based on any gift exchange, it is purely out of consensual love. In a contract like marriage, such things are difficult to prove. Moreover, the way these cases are treated reflects the political ideology and brazenness of the executive. Hadiya’s marriage and how the police handled it is a case in point. Further, these legislations fail to take into account the fundamental right to privacy as observed in the Puttaswamy judgement (which includes the right to sexual choices) and also violate the right to profess any religion and the right to equality. Our Constitution in chapter 3 guarantees every individual, person, citizen to make choices in the domain of their private life. These include personal intimacies, home, and sexual connotations, personal choices that govern an individual’s way of life, privacy. The state cannot be given control of private aspects of any person’s life, and all kinds of heterogeneity are permissible.

These short steps produce and reproduce ideal citizens of the Hindu Rashtra.

An answer to such social and political projects can perhaps be reinforcing secularism in a different way. The concept of the state maintaining a principled distance is not working. Bhargava (2007, 7) argues that the western or the dominant form of secularism which calls for a strict separation of the state from religion is not suited to the Indian context. Rather, the variant which the Constitution makers adopted is more appropriate. Instead of viewing it as having a ‘principled distance’, it is more apt to take it as following ‘non-establishment’ (Ibid. 8). We cannot do away with religion and relationships in the public sphere altogether. As the Supreme Court said, ‘personal relationships are [the] core of plurality in India’ (Web source 4, Scroll.in 2018).

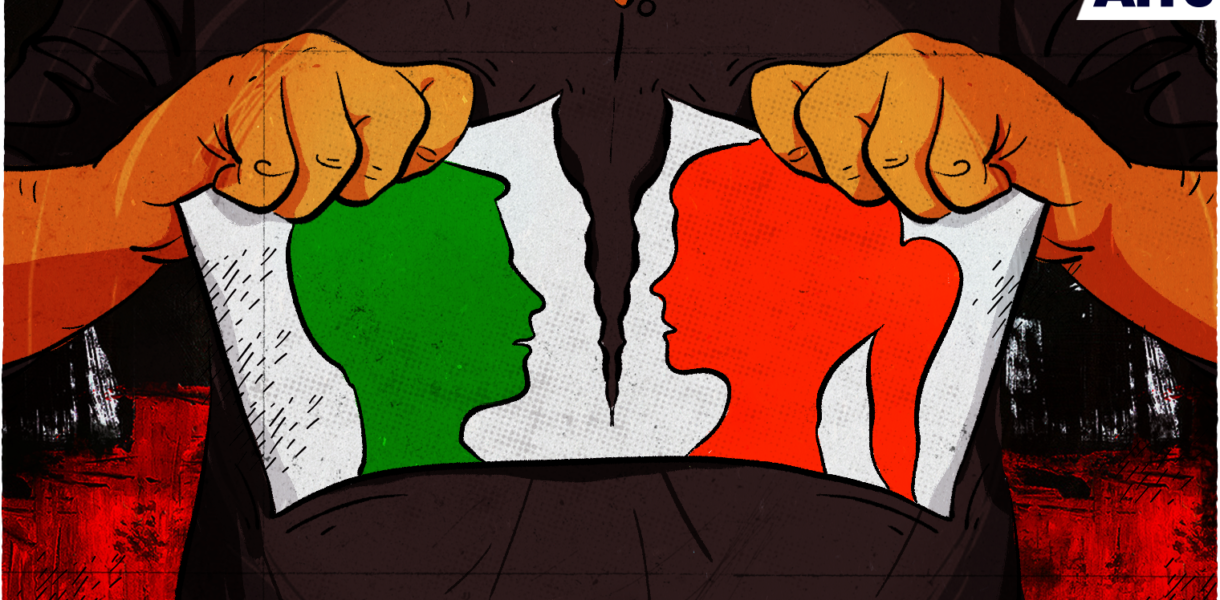

Photo Credits: Arre.co.in

References

Bhargava, Rajeev, and T. N. Srinivasan. “The distinctiveness of Indian secularism.” The Future of Secularism, Oxford University Press, New York (2007).

Chakravarti, Uma. “Conceptualising Brahmanical patriarchy in early India: Gender, caste, class and state.” Economic and Political Weekly (1993): 579-585.

Gupta, Charu. “Hindu women, Muslim men: Love Jihad and conversions.” Economic and Political Weekly (2009): 13-15.

Web Source 1: “‘Love Jihad” Is an Islamophobic Campaign: Why Honour Is about Controlling Women’s Bodies.” 2015. Economic and Political Weekly 50 (23): 7–8.

Web Source 2: “Kerala High Court Finds Signs of ‘Love Jihad’, Suggests Law Checks It.” 2009. Dnaindia.Com. December 9, 2009. https://www.dnaindia.com/india/report-kerala-high-court-finds-signs-of-love-jihad-suggests-law-checks-it-1321955.

Web Source 3: Express Web Desk. 2020. “How Do the Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Himachal ‘Love Jihad’ Laws Stack Up.” The Indian Express, December 30, 2020. https://indianexpress.com/article/india/how-do-the-madhya-pradesh-uttar-pradesh-himachal-love-jihad-laws-stack-up-7126163/.

Web Source 4: Scroll Staff. 2018. “‘Personal Relationships Are Core of India’s Plurality’: Supreme Court Restores Hadiya’s Marriage.” Scroll.In. March 8, 2018. https://scroll.in/latest/871253/personal-relationships-are-core-of-indias-plurality-supreme-court-restores-hadiyas-marriage.

This paragraph provides clear idea designed for the new visitors of blogging, that actually how to do blogging

and site-building.

It’s going to be ending of mine day, but before ending I

am reading this enormous post to improve my know-how.

it is a nice page